Ottoman Fragrance

Each Ottoman sultan had a personal passion for perfumes, as well as a fine-fragrance culture at large.

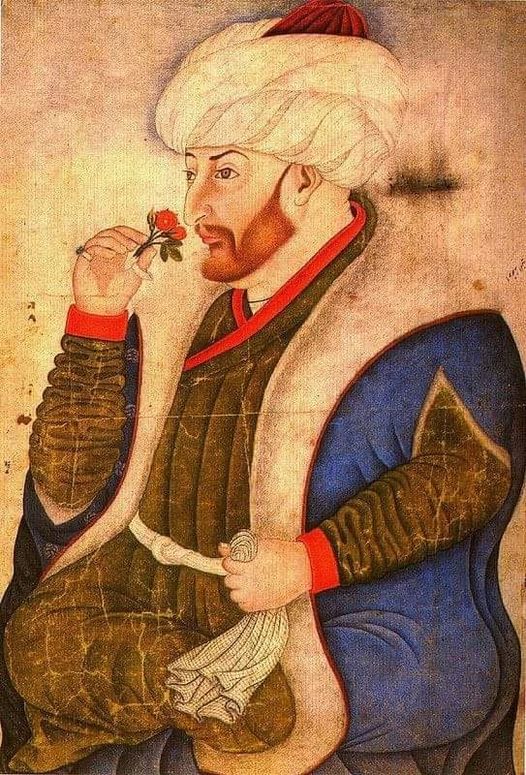

From Sultan Suleiman’s love of sandalwood to Sultan Selim’s soft spot for amber and sweet aromas to Sultan Mehmet’s preference for violet, fine perfume was a ritual necessity among Ottoman royalty that also trickled through everyday life.

Did you know about the mother of the Empire, Hurrem’s Sultan’s passion for jasmine, roses, lime, and clove? (If only she could smell those aromatics lacquered over Tonkin musk-infused vetiver…) Or that, like Sultan Qaboos, Sultan Abdul Hamid donned a melange of oud and rose on Fridays? What about Sultan Abdul Hamid II’s fondness for mimosa?

Not only was it written down and preserved but visit Topkapi Palace and you can actually see the recipe for the Ottoman incense water (a.k.a. buhur suyu) that was as integral to Ottoman ceremonies as frankincense was in churches.

Abdul Hamid II personally backed Ahmet Faruki’s cosmetics shop, which became the bedrock of the fragrance industry throughout the empire. He then later encouraged Faruki to focus on creating colognes designed around Turkish culture.

Oud, musk, and amber, were adorned not just by sultans and viziers, but by folks at home where oud chips were burned and coffee was laced with amber. Before some new mosques opened, they were washed with rosewater.

Perfume was as much part of the fabric of Turkish culture as its coffee is today. Whenever you hear talk of ‘ghalias’ remember that many of these throughout history were ghalias that were made for Ottoman sultans…

The lasting perfume culture established by the Ottomans was inspired by the prophet Muhammad’s (peace and blessings be upon him) love for fine fragrance and the religion’s emphasis on cleanliness. Inheriting this tradition from the prophet and his companions, scents and perfumes were much more than a mere mundane aspect of life.

Nadim Dervish

Sultan Mehmed II of Turkey; smelling a rose, from the Sarayi Albums, c. 1480

Portret i Sulltan Mehmedit II duke nuhatur një trëndafil. 1480. Nga Nakkaş Sinan Beu, miniaturist osman dhe piktor i oborrit i shekullit XV.

Portrait du Sultan Mehmed II sentant une rose. 1480. Par Nakkaş Sinan Bey, miniaturiste et peintre de cour ottomane du XVè siècle.

العربية: السُلطان محمد خان الثاني “الفاتح” يستنشق عبير وردة، رسمٌ مأخوذ من ألبوم السراي المحفوظ في إسطنبول.

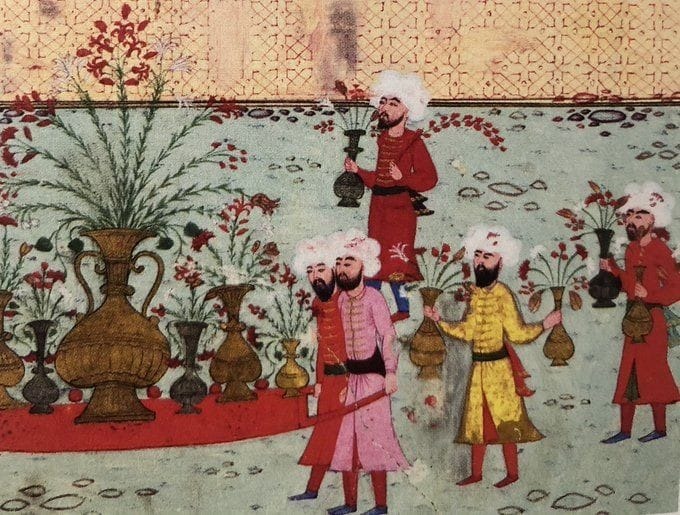

Flowers in Ottoman Empire

Flowers decorated private and public spaces; their representations embellished everyday Ottoman objects such as textiles, tiles, metal and woodenware, books, wall decorations and even gravestones; lower symbolism was frequently used in poetry, the popular culture of the period.

Royal gardens, bazaars, lower shops, were different types of channels used for marketing flowers that made them available and accessible many people who wanted to experience the aesthetic pleasures and symbolic meanings associated with flowers. A decree issued in 1595 states that the number of flower shops selling flowers and fruits increased illegally from 5 to more than 200 in Istanbul, and the governor was ordered to maintain only five of them. Later, in the seventeenth century, the Turkish traveller Evliya Çelebi noted that there were 80 lower shops in Istanbul, in addition to peddlers selling flowers.

In addition to flowers themselves, representations of flowers on everyday objects proliferated, were marketed, and became part of everyday consumption. From the mid-sixteenth century, Turkish decorative arts achieved great success in the use of naturalistic floral and vegetal motifs. In particular, depictions of flowers and bouquets became popular in miniatures which were mainly produced by court artists. These floral styles and designs were transferred to a variety of media by the palace artisans and then trickled down to the public through professional craftsmen in the bazaars. The colourful displays of lowers in the palace gardens must have formed a source of inspiration for the court artists.Tulips, hyacinths, carnations, roses and other lowers appear in the decorative arts of the period, such as wall tiles, ceramics, textiles, kilims (lat rugs) and carpets, painted decorations, court embroideries and fabrics.

This trickle-down process allowed the elite fashion and aesthetic taste based around lowers to spread to the lower ranks of society. Enthusiasm for flowers and their popularity precipitated the introduction of novel products to the Ottoman market. Poetry notebooks with lower decorations were introduced in the seventeenth century for consumption by poetry lovers. Workshops in Edirne, the old capital of the Empire in eastern Trace, produced empty notebooks with pages decorated with handmade lower pictures, using a style specially developed in the city. Later, this local style was applied to woodwork and book binding, and spread to other cities around the Empire. The notebook is ornamented with popular flowers of the time, such as tulips, hyacinths, carnations, daffodils and roses or bouquets with a naturalistic style, in very vivid colours. Not only were lowers sold in the domestic markets but also lower seeds and bulbs were marketed via interregional trade routes.

For example, the tulip entered Asia Minor with the migration of Turks from Central Asia. New cultivations of tulips became popular during the sixteenth century. The French physician Belon, who visited Istanbul in 1546, states that many foreigners arrived in Istanbul by ship to purchase tulip and lower bulbs.

In the seventeenth century, the tulip’s journey to the West from the Ottoman lands generated the famous Dutch tulipomania. It became part of everyday Dutch life, consumed as an exotic and luxury item by the Dutch middle classes. Dutch paintings dating back to the period depict everyday home scenes with tulips. By the eighteenth century, tulips which were cultivated in Holland travelled back as a luxury to be consumed by Ottoman lower enthusiasts. Akin to tulips, garden styles also spread among different cultures within the region.

The culture formed around lower consumption in the Ottoman context demonstrates parallels with the characteristics of late Renaissance culture in the Mediterranean region. In the sixteenth century, Ottoman women’s lower consumption patterns resembled that of their Genoese counterparts living in Renaissance Italy. Renaissance gardens in Italy had their background in the Ottoman garden style rather than the gardens of antiquity, which, in general, was the inspiration for Renaissance culture. Flower depictions of Ottoman arts and material culture utilised the idealised naturalism of Renaissance art. The individual Ottoman flower cultivator who was interested in aesthetics, science, innovation and sharing his accumulated knowledge through writing. These similarities with Renaissance culture demonstrate that flower marketing and consumption in a non-Western culture within the Mediterranean region bothshapedthe regional culture and was shaped by it. Although Western scholarship constructed Renaissance as the speciicity of the modern Western development, Renaissance culture was co-constituted through the interactions of multiple cultures – Western and non-Western – at the level of everyday market and consumption practices.

Eminegül Karababa

the flower sellers’ guild*

İstanbul, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu

- The guild in Ottoman times can be defined as an association of craftsmen and tradesmen who dealt with the same products and who banded together for their mutual benefit.

A S P E R S O I R

Un aspersoir est un récipient utilisé pour asperger un liquide, en général un parfum et principalement dans les pays de l’Islam. Souvent de couleur bleue, couleur prisée, leur forme est bulbeuse sur une base concave avec un long col étiré se terminant par un bec verseur. Ces récipients servaient à conserver des parfums qu’on aspergeait sur les invités à leur arrivée à une cérémonie ou autres grandes occasions.

ensemble de trois aspersoirs à parfums en opaline de Beykoz, XIX ème siècle, İstanbul

La fabrique de Beykoz, établie dans ce quartier d’İstanbul à l’époque ottomane, était la verrerie la plus importante de son époque. Le bâtiment historique du musée a été construit par Abraham Pacha, qui était le gardien du khédive égyptien Ismail Pacha et a été promu vizir par le sultan Abdülaziz.

Create your Own Oriental Turkish-Ottoman Perfume

18 February (15:00 – 17:00) at the gallery Les Arts Turcs in Sultanahmet, İstanbul.

Les Arts Turcs – Art Gallery & Studio

Alemdar Mah Incili Çavus Sok.

No: 19 Floor : 3 Sultanahmet 34400

Istanbul, Turkey

info@lesartsturcs.com

www.lesartsturcs.com

Instagram

lesartsturcsofficial

Mr. Alp – Mr. Nurdogan

Tel and Whatsapp +90 544 220 10 22 / +90 212 527 68 59